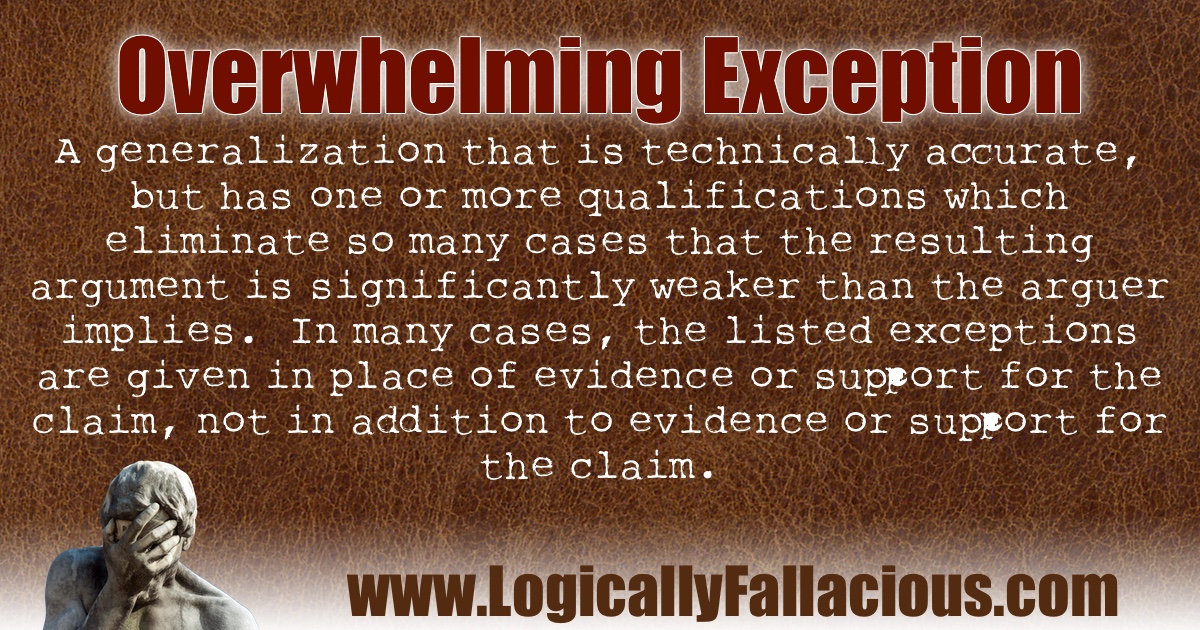

Description: A generalization that is technically accurate, but has one or more qualifications which eliminate so many cases that the resulting argument is significantly weaker than the arguer implies. In many cases, the listed exceptions are given in place of evidence or support for the claim, not in addition to evidence or support for the claim.

Logical Form:

Claim A is made.

Numerous exceptions to claim A are made.

Therefore, claim A is true.

Example #1:

Besides charities, comfort, community cohesion, rehabilitation, and helping children learn values, religion poisons everything.

Explanation: Besides being a self-refuting statement, the listing of the ways religion does not poison everything, is a clear indicator that the claim is false, or at best, very weak.

Example #2:

Our country is certainly in terrible shape. Sure, we still have all kinds of freedoms, cultural diversity, emergency rooms and trauma care, agencies like the FDA out to protect us, the entertainment industry, a free market, national parks, we are considered the most powerful nation in the world, have amazing opportunities, and free public education, but still...

Explanation: We have many reasons supporting the opposite claim -- that this country is in great shape still, or at least that it is not in terrible shape. By the time all the reasons are listed, the original claim of our country being in terrible shape is a lot less agreeable.

Exception: The fewer exceptions, the less overwhelming, the less likely the fallacy.

Fun Fact: This fallacy is usually made by people who are well on their way to seeing the reasonable conclusion in the argument, but can’t quite let go of their unreasonable belief or claim.