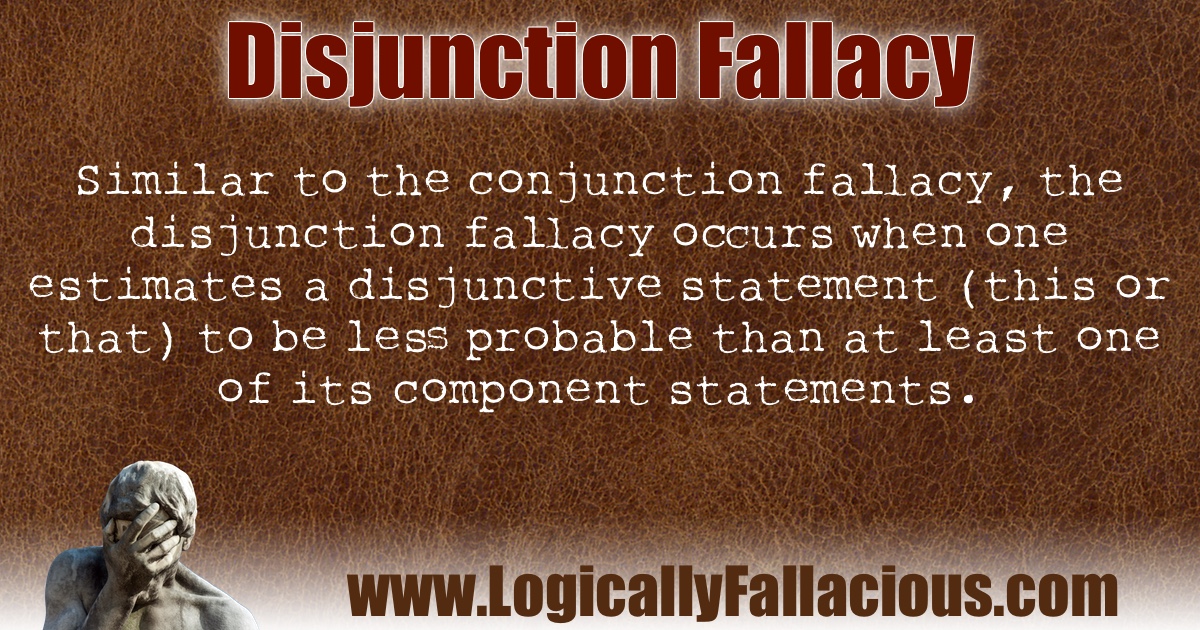

Description: Similar to the conjunction fallacy, the disjunction fallacy occurs when one estimates a disjunctive statement (this or that) to be less probable than at least one of its component statements.

Logical Forms:

Disjunction X or Y (both taken together) is less likely than a constituent Y.

Example #1:

Mr. Pius goes to church every Sunday. He gets most of his information about religion from church and does not really read the Bible too much. Mr. Pius has a figurine of St. Mary at home. Last year, when he went to Rome, he toured the Vatican. From this information, Mr. Pius is more likely to be Catholic than a Catholic or a Muslim.

Explanation: This is incorrect. While it is very likely that Mr. Pius is Catholic based on the information, it is more likely that he is Catholic or Muslim.

Example #2:

Bill is 6’11” tall, thin, but muscular. We know he either is a pro basketball player or a jockey. We conclude that it is more probable that he is a pro basketball player than a pro basketball player or a jockey.

Explanation: This is incorrect. While it is very likely that Bill plays the B-ball, given that he would probably crush a horse, it is statistically more likely that he is either a pro basketball player or a jockey since that option includes the option of him being just a pro basketball player. Don’t let what seems like common sense fool you.

Exception: No exceptions due to basic probability.

Tip: Go back and read the entry for the conjunction fallacy again and make sure you know the difference.